2023 HOLDING IT TOGETHER

FEBRUARY 24th, 2023

Curated by Jake Kimble

Michelle Sound

(b. 1977 Vancouver, BC; Cree, Métis)

Michelle Sound is a Cree and Métis artist, educator and mother. She is a member of Wapsewsipi Swan River First Nation in Northern Alberta. Her mother is Cree from Kinuso, Alberta, Treaty 8 territory and her father’s family is Métis from the Buffalo Lake Métis settlement in central Alberta. She was born and raised on the unceded and ancestral home territories of the xwmƏƟkwƏýƏm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish) and SƏĺílwƏtaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations where she currently resides and works.

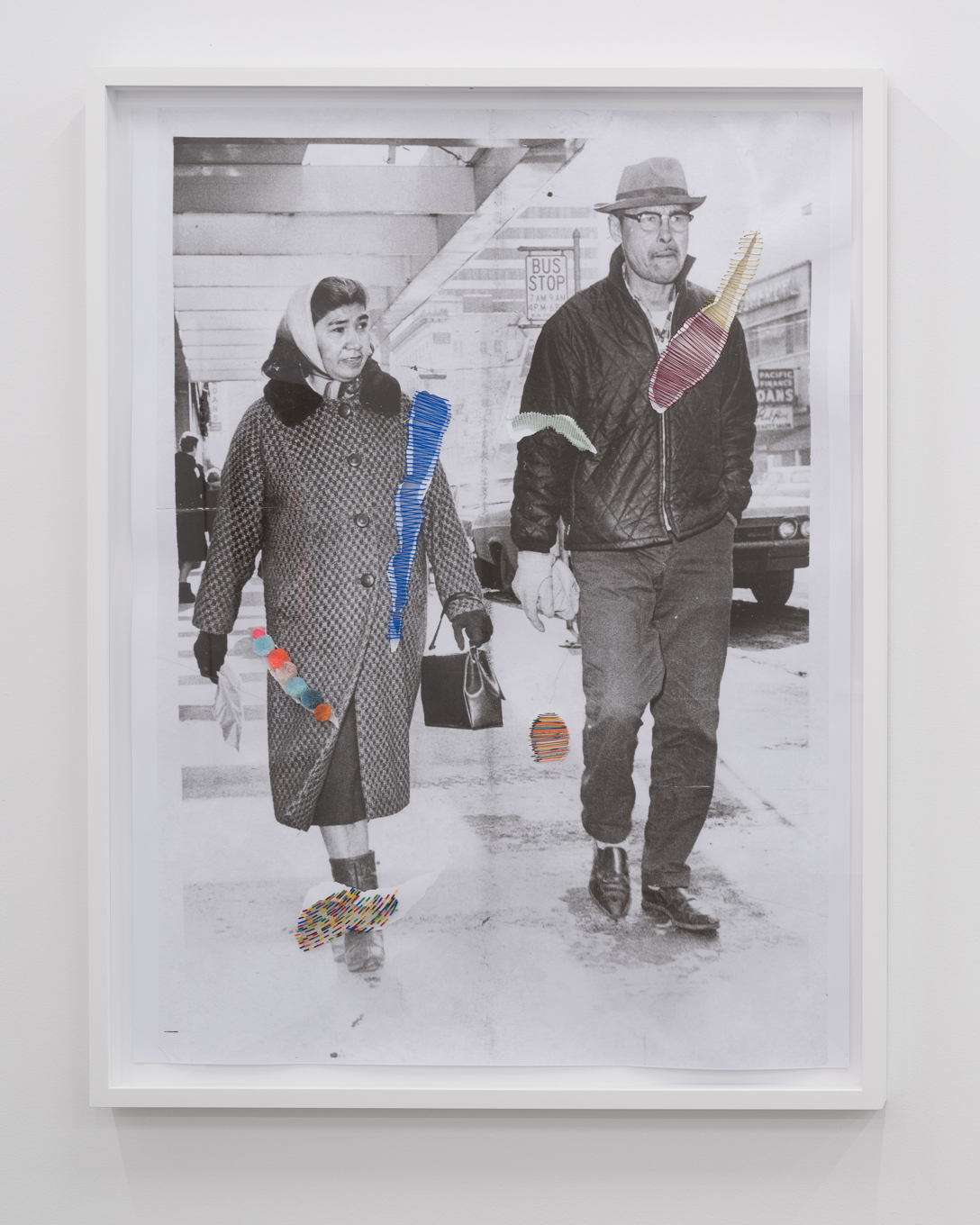

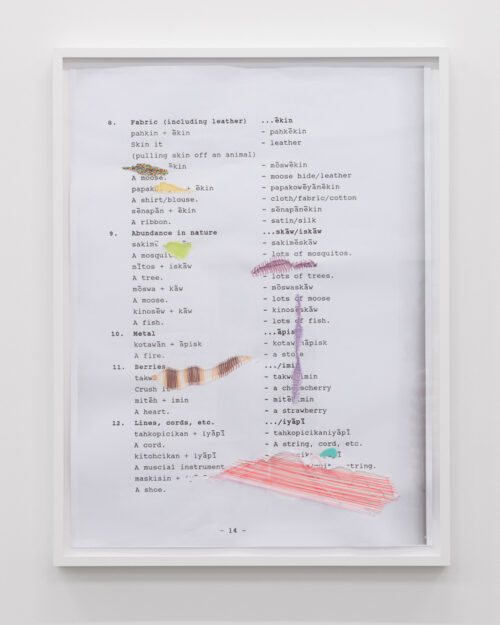

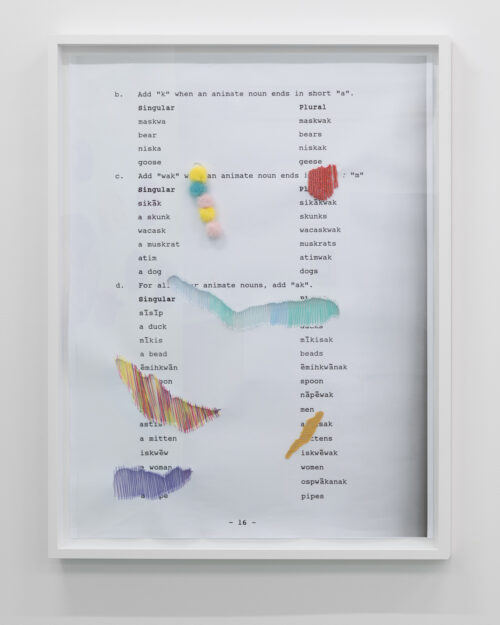

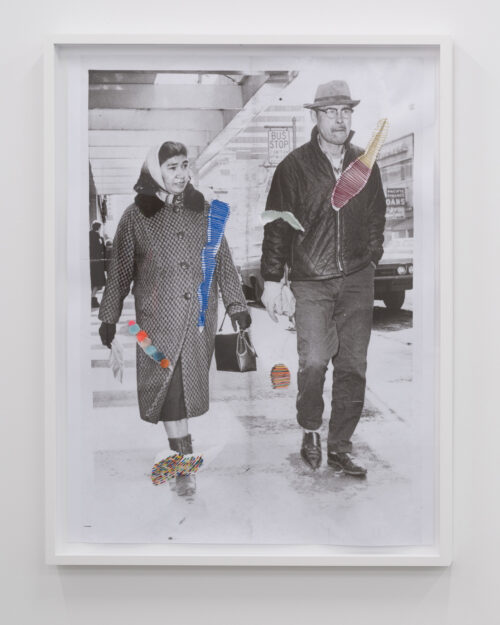

Michelle’s latest exhibition Holding It Together is a mixed-media series that features nine large-scale monochromatic photo reproductions from the artist’s personal archive; pictures of her and her kin, her home territory, and scans from the dictionary from where she learned the Cree language. Each of the images have been torn and damaged at first, but then found repair through traditional ways of art-making; beading, quillwork, stitching, and caribou hair tufting are all at play throughout the series, serving as a visual representation of how the artist has co-existed and continues to co-exist with the effects of colonization.

The exhibition space exists and operates on the traditional and unceded territories of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), səl’ilwətaɁɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) Nations.

NDN Vulnerability: Michelle Sound’s Art of the Long Twentieth Century

by Billy-Ray Belcourt

We are all citizens of the long twentieth century. It never ended for NDNs. I’m interested in methodological approaches to the study of the colonial past that imbue Indigenous peoples in the present with futurity. Michelle Sound’s Holding It Together demonstrates a way of attending to the past that doesn’t result in self-destruction.

Yes, history endures; yes, we are still living out the terror of the long twentieth century—the traumas of settlement, reservization, residential schooling, child abductions, and so forth. Sound’s work takes up these traumas as objects of analysis. She writes, “These images contain loss, grief, longing, and memory… The images are ripped to show the colonial violence that my family and other Indigenous families have experienced.” In Holding It Together, ancestral territory is also a wound; old family photographs, though seemingly ordinary, depict the subtleties of colonial dispossession. A Cree dictionary is also an inventory of loss.

To view Sound’s work is to inhabit paradox. We have to think paradoxically. Which is to say that we recognize that sometimes our desires are impossible or laden with difficulty but we desire all the same. It also means that we have to believe that it is possible to confront history’s atrocities and not be ruined in doing so.

Sound destroys her objects in order to repair them. I understand this approach, I feel it in my body. Maybe it is an NDN coping mechanism, a way of reckoning with grief and holding onto the present even if we know that the present is a dead end.

The torn photographs are stitched with colorful threads and embroidered with beads and caribou tufts. Set against the greyscale photographs, the materials, which meld traditional and contemporary techniques, evidence an aesthetics and practice of care. A torn photograph is a synonym for the past as well as the present. Some nights my body feels like a torn photograph—a very NDN feeling. Sound knows that our grief is both private and public. She sanctions our grief. In doing so, the space of the gallery becomes a new emotional landscape.

Holding It Together also amounts to an alternative history of feeling, an entire archive of NDN feeling, to modify Ann Cvetkovich’s phrase. We have to deposit our feelings somewhere; our bodies can only hold so much. Cvetkovich argues that “cultural texts [are] repositories of feelings and emotions” that situate us in a shared context.1 Sound’s exhibition places us in a larger affective world that runs counter to the miserable settler world we usually have to weather. We come together so that we can fall apart. Our NDN vulnerability isn’t subject to exploitation. To be an NDN in an art gallery is sometimes dehumanizing, because we have been treated as objects for so long. Sound’s series and art practice more broadly seem to be an antidote to or corrective for this experience of objectification. Like the photographs, we too are sites of both trauma and possibility. Like the photographs, we are being held together, threaded to one another. Ultimately, Sound is an emotional historian of the future.

1 Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003: 7.

Installation View of Holding It Together, 2023. ,

Installation View of Holding It Together, 2023. ,

Installation View of Holding It Together, 2023. ,

Installation View of Holding It Together, 2023. ,

KIDS,

2022,

39.25” X 51.5”,

MONOCHROME PRINT ON PAPER, EMBROIDERY THREAD, SEED BEADS, PONY BEADS, VINTAGE BEADS

CREE,

2022,

39.25” X 51.5”,

MONOCHROME PRINT ON PAPER, EMBROIDERY THREAD, SEED BEADS, METALLIC THREAD

STRAWBERRY CREEK,

2022,

39.25” X 51.5”,

MONOCHROME PRINT ON PAPER, EMBROIDERY THREAD, SEED BEADS, METALLIC PONY BEADS

KINUSO,

2022,

39.25” X 51.5”,

MONOCHROME PRINT ON PAPER, EMBROIDERY THREAD, SEED BEADS, CARIBOU TUFTING

BIRTHDAY,

2022,

39.25” X 51.5”,

MONOCHROME PRINT ON PAPER, EMBROIDERY THREAD, SEED BEADS, BAKERS TWINE, CARIBOU TUFTING

DICTIONARY,

2022,

39.25” X 51.5”,

MONOCHROME PRINT ON PAPER, EMBROIDERY THREAD, SEED BEADS, DYED FOX FUR

FOSTER CARE,

2022,

39.25” X 51.5”,

MONOCHROME PRINT ON PAPER, EMBROIDERY THREAD, SEED BEADS, VINTAGE BEADS, CARIBOU TUFTING

KOKUM AND MOSUM,

2022,

39.25” X 51.5”,

PRESENTATION BOND PAPER, EMBROIDERY THREAD, SEED BEADS, CARIBOU TUFTING, VINTAGE BEADS, DYED PORCUPINE QUILLS, METALLIC THREAD

SECOND,

2022,

39.25” X 51.5”,

MONOCHROME PRINT ON PAPER, EMBROIDERY THREAD, SEED BEADS, BAKERS TWINE, CARIBOU TUFTING

,

,

,